Sabledrake Magazine

November, 2002

Feature Articles

The Birth of the Tuatha De Danaan

CTF 2187: Choices, Changes, Challenges

Regular Articles

Resources

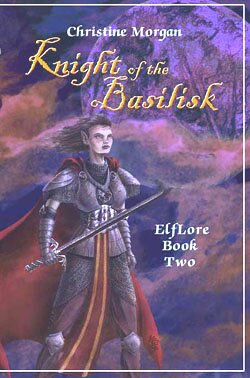

Trial by Fire and Stone

an excerpt from Knight of the Basilisk, the new ElfLore novel

Copyright © 2002 Christine Morgan

A stillness and dread settled over the elves, broken only by the dying sizzle of the flames. But as if their very attention had brought on the disaster, a new sound came in the form of a shifting, rumbling groan. One of the walls sagged inward. A gout of eerie purple fire licked up, and from somewhere within that blackened, smoking mess came a sudden cry of pain.

A stillness and dread settled over the elves, broken only by the dying sizzle of the flames. But as if their very attention had brought on the disaster, a new sound came in the form of a shifting, rumbling groan. One of the walls sagged inward. A gout of eerie purple fire licked up, and from somewhere within that blackened, smoking mess came a sudden cry of pain.

“Falanar!” shrieked his mother.

No one seemed able to move, and in that instant Tilanne fully understood that it all fell to her. She had not been able to save Findaire …

With that thought foremost in her mind, she headed for the ruin. Corandir tried to stop her, but one even look from her was enough to make his hand slip free from her arm. He let her go on unhindered, while the rest looked on in uncertain dismay.

Each step that brought her closer was a step Tilanne would rather not take. She could see it more clearly now, the damage and the danger. A shimmering bank of heat rose from the stones, which themselves looked softened, melted. Here and there, half-buried by tons of rubble, protruded charred sticks that had once been elven limbs.

From within, Falanar cried out again. “Mother … Mother, help! Caught am I!”

“Where?” Tilanne shouted.

“Tilanne, nay, come back,” pleaded Alarice.

She came to an opening. Even the least experienced hunter would be able to follow the fresh tracks in the ash, which led toward a gaping and uneven opening. It was like a mouth, a dragon’s mouth, all darkness and heat with a reddish wavery glow underlying the shadows. Jagged, burnt stumps of beams were the teeth, and a slab of marble was the tongue.

The fortress shifted again, things sliding heavily and unseen. Falanar’s call became an agonized scream, echoed by one of desperation from his mother.

Tilanne flinched back as chunks of stone tumbled from above. The moment they stopped falling, she squinted against the waves of oven-warmth and held her breath against the vile fumes that issued from the forbidding opening. She plunged inside.

Now she knew what the Torments would be like. Terror and confusion and pain beat at her from all sides as she made her way into the malformed remains of a once-lovely fortress. Everywhere she looked, she saw death. Elves robbed of their long lives, robbed of their beauty, robbed of their hope and promise.

Timbers creaked and stone squealed against itself. Tilanne could hardly see but dared not attempt to feel her way, knowing that a single brush against a beam might bring it all down upon her head. She groped with her toes, eyes stinging and watering from the stench of death.

As she pressed deeper, seeking the source of Falanar’s voice - he had progressed now to incoherent moans and sobs, perhaps understanding that no one could reach him - Tilanne felt something new and upsetting. The aether was disturbed.

She was no sorceress as was Alarice, but any elf could sense the patterns of aether. The force that was the lifeblood of magic was as constant and taken for granted as the very air. But in this place, the air itself was twisted and treacherous, laden with poisons that dizzied her when at last her aching lungs compelled her to sip short breaths of it. So too was the aether, twisted and strange, made poison.

Wiping futilely at her streaming eyes, Tilanne saw shafts of discolored daylight ahead. She pondered it for several moments, certain she hadn’t been turned around. She couldn’t have been, because Falanar’s moans still came from somewhere up ahead.

Then she remembered the way the explosion of warped fire had roared through the roof, raining down on the courtyard. Picking her way toward the light, she came at last to what had been Marona’s casting chamber.

Her foot struck a corpse, a woman whose body was half scorched to a cinder. The unmarked side of her face was locked in a grimace, and the tattoos along her scalp as well as the multiple piercings marching the rim of her ear proclaimed her as one of the Crown Mages.

Choking, more from horror than from the stink now, Tilanne’s gaze roamed the chamber.

Candlewax formations of rock, which had melted and then cooled to congeal in strange shapes, turned the floor into a hostile landscape. Shards of thick glass had been driven into the very walls, in one case having pinned the skeletal remains of a robed elf through the chest.

Among the bodies were several in armor, though the black metal had been deformed almost beyond recognition. And the bodies themselves, those ones, looked wrong to her eyes. Even allowing for the damage the fire had done, they looked wrong.

She could not take the time to look further, for she had found Falanar. Or at least she saw part of him, one feebly-moving hand over a pile of rocks and debris. A balcony wall had collapsed atop him, the balcony itself resting in nearly perfect condition as the lid to a tomb, in which the young elf was imprisoned alive.

Tilanne scrambled over the uncertain footing. “Falanar!”

“Ti … Tilanne?”

“Be still, Falanar. Help thee I shall.”

“My father … sought did I my father …”

“Dead are they, dead are they all. Thou knew that.”

“Wished did I to find him … to the pyre bring him … not buried in stone like a dwarf should he be … not left to rot …” He coughed, horribly, wrackingly, too terribly reminiscent of Findaire. Too hurt, too hopeless.

She reached the pile and grasped his hand. His fingers closed on hers with no more strength than an infant. Blisters were rising in white bubbles on his skin, and two of his nails had been torn away to the quick, threads of blood trickling from them.

By moving one of the few stones that did not seem to be supporting any of the others, Tilanne was able to see his face. His eyes were dark holes, pits of fear, and he looked so very young. Seventeen, no older than she’d been when her father had been assigned to Cliffcave Fortress. Too young to die at all, let alone such a death as this.

“Falanar …”

He heard what she couldn’t bring herself to say, and shook his head in negation. “Please, Tilanne. Leave me here thou cannot!”

“If more of the stones I remove, shift shall the balcony atop them and surely crush thee. How severely art thou injured?”

“My leg … my back …”

“Able art thou to move?” She spied a few other pieces that did not seem to be weight-bearing, and pushed them aside. They bounced and rolled in a clatter, and she bared Falanar’s arm.

He did not reply, did not need to when she saw the dismay in his eyes. He was trapped and paralyzed, and the rest of the walls might come down at any moment, and she did not even have Corandir here to do what she could not bring herself to do.

“Lost already so many lives,” Tilanne murmured, touching the knife at her waist. “I cannot … Kaledhol forgive me, I cannot.”

But neither could she leave him to a slow and miserable death. Finding larger chunks and parts of beams, she tried to brace up the balcony while pawing away the heap that held Falanar. He watched her like a rabbit in a snare, helpless but terrified rather than resigned.

Tilanne cast desperately around the chamber, seeking something else to help hold up the balcony or pry away the stones. Her gaze took in the scattered ring of armored figures again, crumpled in a regular pattern unlike that made by the bodies of the mages … almost as if they had fallen before the explosion …

A familiar wink of color caught her eye, and Tilanne caught her breath as she recognized the yellow star sapphire set into the pommel of her father’s sword. Dragon’s Eye, that blade was called, and it had been one of her mother’s last gifts to him before death-in-birthing had carried Vandanne Murres from this world.

She stood, then dropped back into a crouch and shielded her head with her arms as a hail of pebbles pelted her from above. Wincing in expectation, she waited for the inevitable larger missiles. A rock the size of a robin’s egg struck her forearm, another hit the floor and bounced up to crack smartly against her kneecap.

A sliding rumble shook the room. Falanar wailed, and distantly from outside Tilanne could hear the rest of the survivors calling out in alarm.

When the room did not immediately collapse in on them, Tilanne risked rising again. She picked her way across the littered floor and came to the glinting yellow gem.

“Dragon’s Eye,” she breathed.

The sword was still sheathed across her father’s back as he sprawled face down. The finely-tooled leather of the sheath was ashy black flakes that fell apart as she touched it, but the weapon itself appeared undamaged.

There was no time to waste, but she had to look one last time on her father’s face. As horrific as it might be to see him so, she had to.

Setting the sword aside, she grasped him and turned him over. The warped metal was hot even through her gloves. Steel clanged dully on marble as she rolled him to his back, and a scream lodged fast in her throat.

She had been prepared to see him burned, thought she was ready for such a sight. But that which greeted her was so different, so horrible, that for a moment Tilanne was rooted to the spot and oblivious to all around her. The acrid smoky air ceased to bother her, the threatening grind and shift of stones went unheard.

He was Forantil Murres … and yet he wasn’t. The man staring sightlessly up at her was unmarked by burns on his front half, as if he had indeed been in that position before the fireball erupted through the chamber. And looking at him, she could see why, because no one could be so wizened and ancient, and still be alive.

Her father’s hair, what strands of it had escaped from beneath his helm, was the color of parchment-ivory when once it had once been as coppery-red as Vandil’s. His skin was etched with wrinkles, blotched with age-spots, and shrunken against the contours of his skull. His lips were drawn back in a rictus, exposing teeth from which the gums had receded. And his eyes, wide-open and frozen in a glassy stare, were filmed in milky cataracts.

Rare indeed was the Morvalan that lived out his or her natural lifespan. Warfare took the males, birthing took the females, injury and illness took one and all. They did not have the luxury of their spoiled northern cousins, to while away centuries.

The oldest living being Tilanne had ever seen was the sorceress Ensinameline of the Scepter, who dwelt in Deepwater where Tilanne’s sister’s husband was stationed. That nine-hundred plus, diminutive, white-haired woman would have looked young and vital compared to this … this thing before her that wore her father’s features in that shriveled mask of age.

She stared as if spellbound, horror creeping insidiously along her every nerve. After an untold amount of time, at last her surroundings filtered back into her consciousness. Falanar was hitching and whimpering, plaintive and desolate sounds that said he thought himself to be abandoned, left to die slowly and alone.

This thought gave Tilanne the strength to tear her gaze from her father’s desiccated visage. Clutching Dragon’s Eye, she backed away from his body.

“Be thou brave, Falanar,” she said, unnerved at the shakiness she heard in her own voice. But it soothed him, and he quelled his whimpers as she returned to his prison.

Using the sword as a lever, she worked it into the heap and pried apart the larger stones. Soon Falanar’s shoulders and head were unburied, and he clawed at cracks in the floor in an effort to pull himself free. To no avail. Tilanne peered as best she could into the shadows that held him, and saw the rear edge of the balcony pinning his legs.

Her mind was all aswim now, from shock and the impure air. A crash from elsewhere in the fortress shook the ground, and sent new cascades of debris into motion. The opposite wall began to break apart, with the slow grandeur of an iced-over waterfall giving way to the spring thaw.

Falanar cried out, loud and despairing and doomed. Sensing immediacy, Tilanne let go the sword and seized his outstretched arms. She pulled with all her might. The boy’s body moved slightly, him shrieking now as bones were wrenched and skin was torn.

A boulder-sized piece of the opposite wall fell, bounced, passed close enough to Tilanne to whip her hair in the breeze of its passage, and smashed into the corner. The pile that had held up the balcony slid in a jittering and cracking avalanche.

She saw her name on Falanar’s begging lips, the sound of it lost in the hungry roar of the shifting stone. She threw her weight backward, no longer caring if she dislocated his arms or scraped all the skin and flesh from his legs, meaning only to get him out, save him.

The balcony slammed down, its leading edge hitting Falanar just below the shoulderblades and driving him into the floor. As if that wasn’t enough, it teetered side to side, grinding him beneath tons of marble.

Tilanne screamed with him, and sustained hers long after his was abruptly lost in the gout of blood that spewed from his gaping jaws. He went rigid, his hands beating against her in thoughtless panic. She clutched at them, caught one as he went limp. The other slapped against the floor with a lifeless smack.

His eyes slid briefly toward her, but there was no comprehension in them. And even as she leaned forward, shaking her head in mute denial, the spirit drained from them and left them blank, empty orbs.

Numbed and uncaring that the room was continuing to shake itself to pieces around her, Tilanne kissed the back of Falanar’s hand. Only when a careening chunk of stone struck beside her with enough force to batter itself into dust did she suddenly and with a wail of despair and rage come back to her full senses.

She snatched for the hilt of Dragon’s Eye and the hilt was all she got, the blade having been snapped off when the balcony came down. Clinging to it for no sensible reason, Tilanne whirled toward the exit and saw that it was heaped with rubble, only a narrow gap remaining at the top. She ran at it all the same, not bothering to tread cautiously now. She scrabbled up the slope, dislodging several stones and almost sending herself to the bottom in a rockslide, and wormed through the gap with her back scraping against the top of the arched doorway.

The other side was a coalbed now, as the inrush of air had breathed new life into the smoldering fire. Beams and slabs lay at haphazard angles across a long pit of fire, and the ceiling overhead was streaked with jagged, spreading cracks that sifted dust down onto her.

“Kaledhol, please,” she said without realizing she spoke aloud. “Not ready am I … the chance allow me the Kai’s choice to honor … if Thy will it is, let me this place escape, and swear shall I to Thee that never by my hand shall elven life be lost, and pledge always shall I elves to defend.”

Tilanne stepped onto the end of the nearest beam and crept out over the expanse of hot orange, all too aware of what a misstep would mean. The wood smoked beneath her boots and she could feel the heat through the soles. Her quick, light breaths turned the lining of her mouth and throat to something that felt as dry and baked-shiny as a pot in the kiln.

As she reached the end of the beam, it dropped joltingly and she went with it. The heavy end kicked up a shower of sparks and flame, and not hearing her own terrified scream, Tilanne leaped.

She landed on a marble slab and it tilted toward her, the slick surface giving her scant purchase as she slipped inexorably back toward the pit. A chance look upward showed her a dangling lattice of wood. A lunge, a grab, and she was suspended above the coals as the thin slats cracked under her weight.

With no more prayers and no more screams, her jaw clenched tight, Tilanne swung from hand to hand along the untrustworthy lattice, splinters from it sprinkling her hair. She got her feet over another slab, this one at a steeper angle but textured with sculpted reliefs of Crown Magic runes.

Not bothering to worry what spells she might unleash by stepping on the symbols, she scaled it as if it were a rough hillside. She reached the top and saw a clear expanse of hallway leading deeper into the cliffside, and a partially-blocked rat-warren of a hallway leading the way she wished to go.

She chose the blocked way, squeezing past and around and under the obstacles. Ahead was daylight, dimmed again by dust and smoke.

Her shoulder bumped a beam. Tilanne dove forward as a tremendous deadfall crash jolted the hall, and looked back gasping to see that it had missed her feet by too close to consider.

There was no time to congratulate herself, for the ceiling was quaking and spilling steady streams of gravel. Springing up, Tilanne dashed forward although her every muscle strained and hot stitches dug into her side.

The ceiling caved in with a coughing roar, and Tilanne was thrown headlong into the courtyard in the midst of a billowing cloud of dust and soot. She struck with bone-jarring force and was barely able to cover the back of her head before she was overwhelmed by a flying shower of wood and stone.

Gradually, she realized that she was still alive and that the sounds of destruction had diminished, like a thunderstorm passing into the distance. She heard voices calling her name. Dazed and aching, she couldn’t answer, could only stay where she was as the others frantically pulled things off of her.

The next thing she knew, she was being helped to her feet by Corandir and Jedriel. She swayed and they supported her, and she gagged and spat to clear her gritty mouth.

“Falanar?” asked Falana tremulously.

Tilanne shook her head, tears streaking the dust that coated her face. “Trapped he was, and save him I could not.”

A mournful, anguished sob burst from Falana. She fell to her knees, rending her hair and keening her grief, as young Mivana looked on uncomprehendingly and Vanfal cried in his basket.

“For his father had he gone, who like mine a soldier was,” Tilanne said to Corandir. A convulsive shudder went through her. “In the casting chamber … dead were they, Corandir, before even the fire came. What … what to them was done?”

“Know do I not,” he said, and touched the bandage over his eye. “Resting in the infirmary was I then, when summoned were the rest by the Kai.”

As if for the first time, Tilanne looked at him and saw him, saw how he was consumed by pain and refusing to show it. She steeled her own spine and pushed the ghastly image of her father from her mind.

Jedriel took her by the upper arms. “Tilanne, done that thou should not have … too great a risk was it. Lost as well could thee have been.”

“True he speaks,” shrilled Olithiana. “If any had gone, a man should it have been.”

“Gone would I have,” said Sahen huffily. “The chance I had not, so quick and impetuous was she.”

“Pfff,” snorted Reshelli. “Man, not boy … and what of it? At least alive Tilanne emerged. Could you have the same accomplished?”

“Verily.” He flushed scarlet, glaring at her.

“For thee, fine it is thy life to throw away,” Olithiana said to Reshelli. “Barren thou art, and thus no true woman. But Tilanne young and vital is, and best shall her people serve as a woman ought. By marrying, by bearing many children our numbers to replenish. Now more than ever, needed is such.”

Sahen pounced on that eagerly. “And so no Rhunvala should she become, plainly.”

“Kai Terindor wed was,” Corandir said. “Died long ago did his wife, but live on still do his children. No law is it that the Rhunvala marry not.”

“Different it is for women,” said Olithiana. “Hazardous enough is childbirthing, and moreso if with combat she life and limb endangers. Thus is no woman to arms training permitted.”

Reshelli, fuming, thumped the ground with the butt of her spear. “If so great a proponent of motherhood art thou, explain to me do why no children yet have thee.”

“No compassion have thee?” cried Falana. “Dead lies my son, and over such things thou bicker? Unsafe is this place, cursed is this place, and away from it we should before more of us into death my poor Falanar follow. Two children have I yet, and not a moment longer here will I keep them.”

“So it is,” Tilanne said, although every fiber of her being cried out for a rest. She brushed off, only then noting that somehow she had tucked the broken hilt of her father’s sword inside her tunic. She found it fetched up near her belt, and fished it out. “Leave for Jewelgreen we must, and now.”

They had been prepared to depart when she’d gone in search of Falanar, and so only moments later, the small group of them headed for the drawbridge. Vennan led the horses, with the children perched in the cart while Ninare walked alongside. Sahen insisted on leading the way, and with Ninthar’s help was able to wrestle the heavy gates open enough to admit them.

Tilanne was the last one out, and turned to look at the fortress that had been her home for over a dozen years. She would have given much to be able to blink and have it back as it had been, to be able to go to the apartment she shared with her family. To have life be as it always had been, when her most pressing problem was the very one that Olithiana had voiced - which prospective suitor her father would choose for her, and how many of their children would survive. But she did not waste time wishing for the impossible.

“As thou wished, noble Kai, so shall I do,” she promised in a whisper. “Fail thee shall I not. Though know do I that thou might otherwise have wished it, I do pledge thy trust to earn, and that cause to regret thy choice shall thou never have.”

**